'Dust Bunny' review: Bryan Fuller makes feature debut with fearsome, fanciful fairy tale

When I first saw the trailer for Dust Bunny, I wondered how it got made. An original concept from mad queer genius Bryan Fuller with the great Dane Mads Mikkelsen in the lead role. Not who you might expect to be an American action hero, he’s more typically cast to have his dastardly plans foiled by James Bond, Doctor Strange, or Indiana Jones. He achieved a cult following thanks in no small part to NBC’s series Hannibal, and he led the film Another Round to an Oscar for Best International Feature. I think he’s charismatic as fuck, a natural movie star, but he’s not quite a household name, so who gave these people the money to do this? God bless them. Or whatever is atheist for “God bless them.”

Fuller masterminded Hannibal. He also brought ABC’s Pushing Daisies to the screen. And his first season of Starz’s American Gods was a stunner (he departed the show after that, and it became mired in behind-the-scenes controversy). That gives him a blank check from me as a viewer. I’ll watch anything he makes. And if I ever become a Mega Millions billionaire, I’ll give him an actual blank check. Just shut up and take my money. Fuller is one of my favorite creatives currently working in visual media, so I was giddy that Dust Bunny was his brainchild — his feature film directing debut, in fact. It’s a weird, morbid little fairy tale. It’s not the best thing he has ever made, but boy am I glad it exists.

The film doesn’t explain itself upfront, so it takes some time to gain your footing. There’s a girl, Aurora (Sophie Sloan), who is afraid of a monster under her bed that no one else believes in, but she hears her parents screaming one night and then they disappear. There’s also a mysterious, unnamed neighbor (Mikkelsen) whom Aurora witnesses laying waste to a gang of miscreants in Chinatown. He’s clearly dangerous, so she decides to hire him to take care of her monster problem. But is the creature real or a figment of the traumatized girl’s imagination? For that matter, did Aurora really see what she thought she saw in Chinatown?

The film withholds some of its answers for longer than feels natural or necessary, but in the meantime we get to enjoy production design by Jeremy Reed that’s elaborate and fanciful, walking a fine line between the real and fantastical. The night scenes — and there are a lot of them — are a little too murky at times to fully enjoy the details, but Fuller nevertheless demonstrates a keen eye. His work is always more beautiful than it needs to be, offbeat but impeccably styled. Even the grisly murder tableaux from Hannibal were composed with artistic flair. Consider Dust Bunny’s seemingly extraneous details, like light fixtures that form halos behind characters’ heads, a bull statue that Aurora rides to avoid touching the dangerous floor, or a particularly odd chicken lamp. The film could probably do without them, I suppose, but they delight, so there’s no need to justify them.

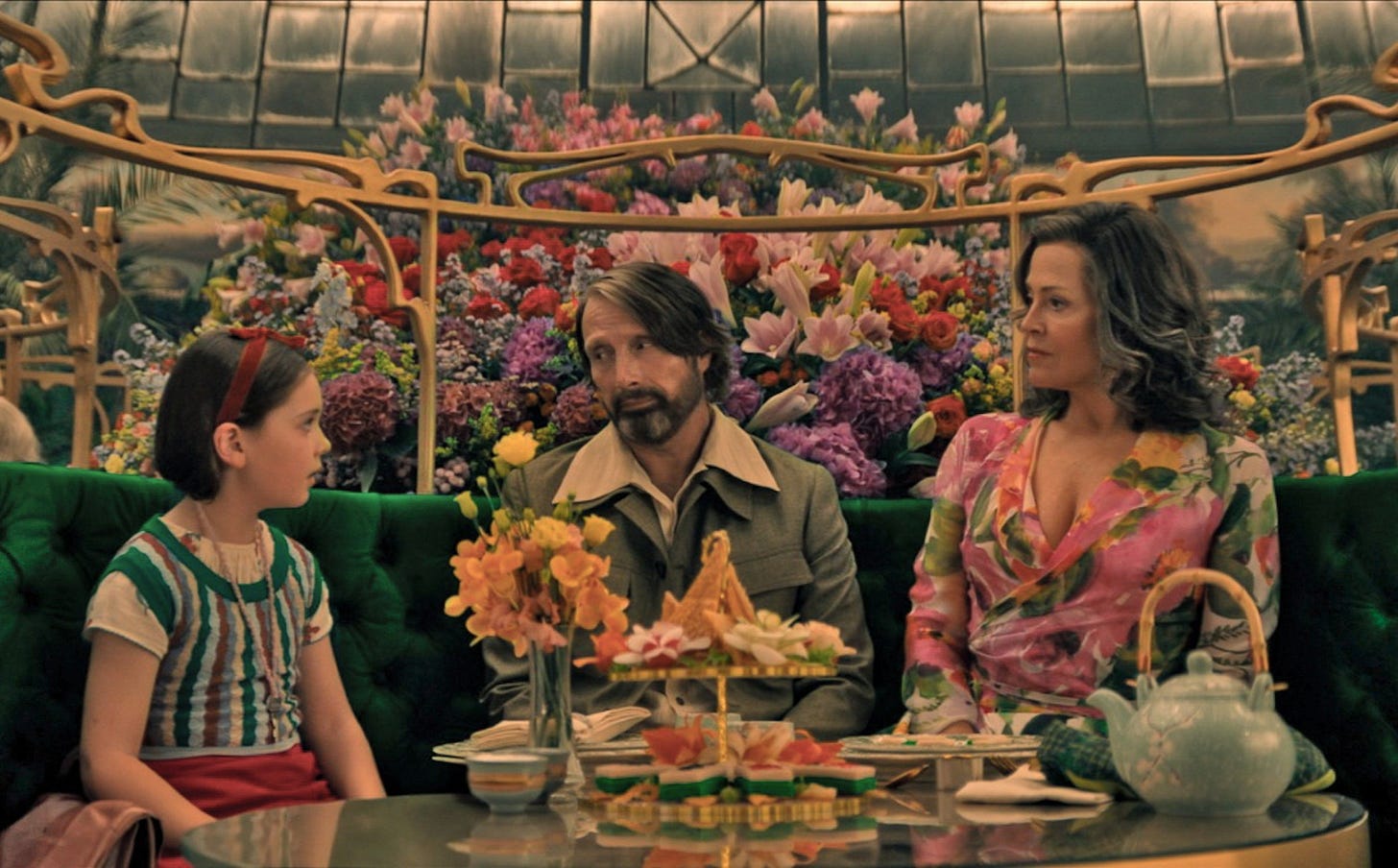

But while the film is ornate in its visual design, it’s economical in its storytelling. There are few locations, spare plot developments, and limited characters (also including Sigourney Weaver as Mikkelsen’s handler of sorts and David Dastmalchian as one of Mikkelsen’s sinister enemies). That enhances the film’s effect. Fuller achieves the simplicity of a children’s story but doesn’t hold back from the intensity of childhood fears; the film is rated R for violence, after all, so it’s probably more appropriate for adult viewers’ inner children than it is for actual little ones, though some tweens may be mature enough to handle it, if not to parse its more grown-up themes.

“A little background. I grew up with an abusive father, and I would have been content to have him eaten by a monster,” explains Fuller in a director’s statement from the film’s production notes. So too did Aurora wish for a monster to devour her family. Now she feels guilty for making that wish, doesn’t believe she deserves a family, and expects the monster to finish the job by finally eating her. The neighbor also believes in monsters, but only the human variety, which is the kind that afflicted Fuller in his youth. “If there is a conversation around Dust Bunny, I hope it is about listening to children and hearing what they may not be saying with words, but might be screaming in other ways.” Whatever the nature of the monster, the girl’s fear is real. The neighbor helps her because he believes he led his own monsters to her doorstep, but what matters is that he shows up, and it would mean even more to her if he stays.